Fortitudene vincimus.

By endurance, we conquer.

- Shackleton family motto.

On August 8, 1914, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition with a crew of 27 men (including one stow-away) set sail from England with the goal of crossing the icy Antarctic continent on foot. As fate would have it, their ship, Endurance, perhaps one of the strongest wooden ships ever built, became stuck in the unforgiving pack ice of the Weddell Sea. The crew spent the winter of 1915 aboard the boat but were later forced to flee the ship when she was crushed by the ice. Thus begins their four month odyssey floating on ice-floes, bored to death with nowhere to go, hoping the current would carry them far enough north to reach nearby islands. When the floe deteriorates the men took to three boats to reach the nearest island. 50 sleepless, starved, dehydrated, and freezing hours later, the men safely made it to Elephant Island, touching land for the first time in 497 days.

But they weren’t safe yet. Elephant Island is a harsh, weather and sea-beaten island where rescue is unlikely. Shackleton decided that he and five others would take a boat to sail 850 miles to South Georgia Island, the nearest beacon of civilization, where they would enlist a ship to rescue the men at Elephant Island. Shackleton had his doubts about their chances of success but there was no alternative.

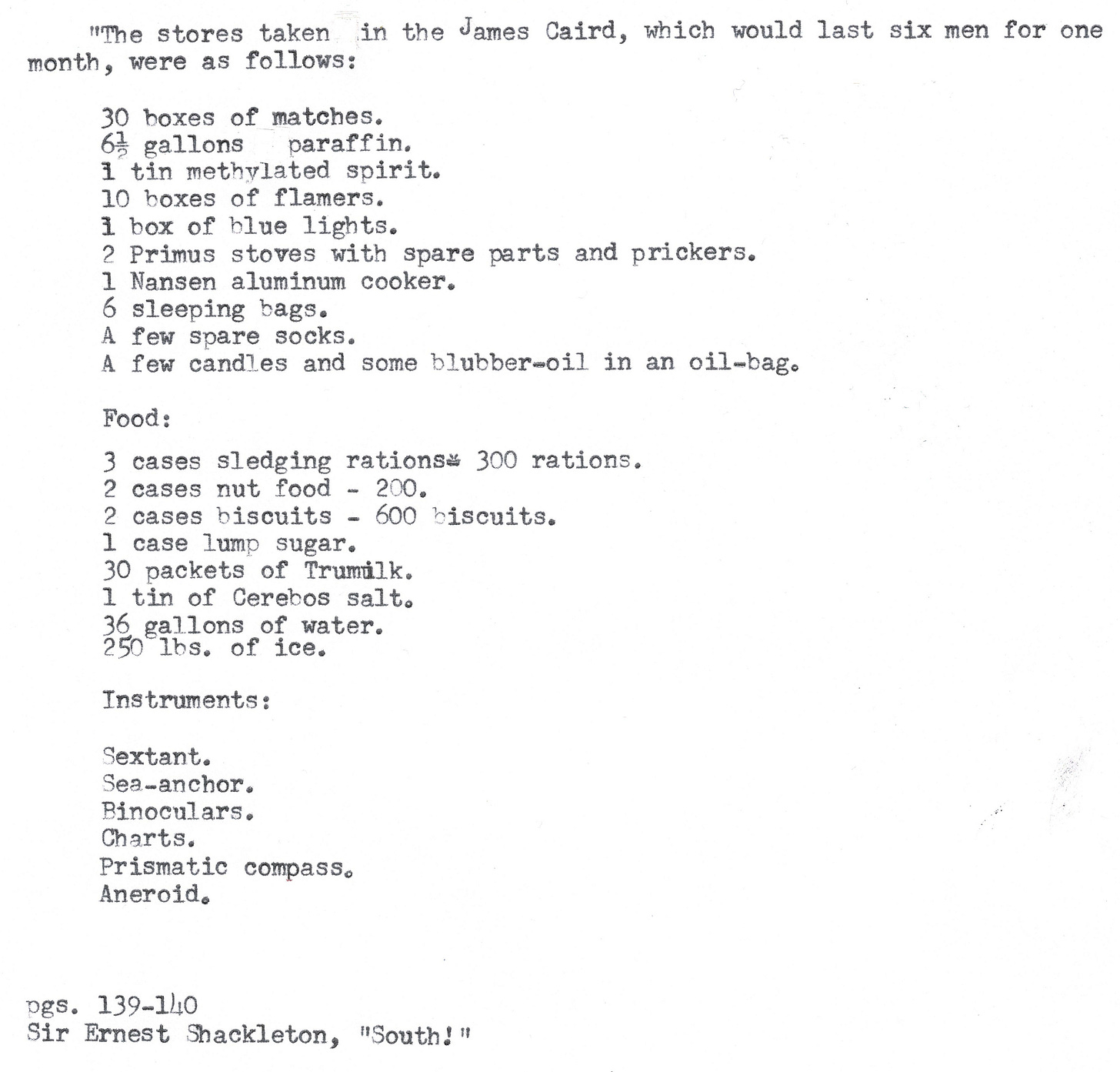

On April 24, 1916, Shackleton and his crew of five set off to cross the infamous Drake Passage. Their boat, the James Caird, was a modified whaler not intended for open ocean sailing. They pack enough food to last six men for one month and equipment necessary to survive the harrowing journey. Along the way hurricane-force winds battered them while waves 80 to 90 feet tall threatened to sink the boat. Freezing ice and snow had to be chipped off the boat so it didn’t weigh them down. The men endured the cold, sleepless nights, and dehydration.

Above all they risked being blown off course and never making it to South Georgia. Bad weather made navigation difficult. Shackleton decided to aim for the western side of the island, in case they overshot the whaling outpost to the east. Frank Worsley, captain of the Endurance, proved to be a skilled navigator who successfully guided the boat to their destination. The voyage took 16 days. Upon landing at South Georgia, one last trial remained before they could rescue their men on Elephant Island. Shackelton and two men hiked across the tough interior of the island to reach the whaling outpost. By August 1916, the men on Elephant Island were rescued. Despite the odds, all of Shackleton’s men survived through a combination of Shackleton’s leadership, Worsley’s navigation skills, the men’s optimism and determination, and sheer luck.

Intrepid explorers of their time, they set out to accomplish something no one had done before and instead proved that man could survive in the harsh antarctic. Lansing said it best:

“Though they had failed dismally even to come close to the expedition’s original objective, they knew now that somehow they had done much, much more than ever they set out to do.”

The legendary tale of Shackleton’s Endurance expedition never ceases to capture my imagination. Back in January I read Mensun Bound’s The Ship Beneath the Ice which details the expeditions to locate the Endurance shipwreck, so naturally I had to go back and reread Alfred Lansing’s Endurance. The stories are incredible - from the haunting moaning of the crushed ship, to their observations of the natural world no man will likely ever see again, life on an ice-floe and their intense boat journeys. These accounts have stuck with me ever since I first read the book several years ago and I was just as awe-inspired while reading a second time.

I haven’t read Shackleton’s account South! yet but while flipping through a copy of his book, I noticed a list he included of the food and equipment packed aboard the James Caird for the trip to South Georgia. I typed the list on my typewriter, thinking it’d be fun to see the list printed. As I typed, I wondered what these items were, how they were used, and how they contributed to their success.

What is a list anyway? A list can serve several functions - as a to-do list, grocery list, a checklist, things to remember. When I’m packing for a trip I always make a list which I double-check to see what I need to pack or what I can eliminate.

I’m not sure if Shackleton composed this list simply for his book or if he had actually written the list prior to sailing on the James Caird. Just like anyone taking a trip, he too might have written down things to bring. Always the cautious leader, he would have ensured that each item was absolutely necessary to their survival.

Let’s take a closer look at Shackleton’s list and see what we can learn.

Equipment.

Listed first among the equipment Shackleton brought aboard the James Caird are the all-important matches, which were kept in a watertight container. Matches were used to light the Primus stove and candles, and for taking night-time compass readings. Matches could also be used to signal other boats, as Shackleton did during the trip to Elephant Island when one of the other boats was separated from the group. Matches were used sparingly because Shackleton didn’t want use candles too often since he hoped to save them for when they made landfall.

The next important piece of equipment was fuel to light the Primus stove which ran on methylated spirit, or denatured alcohol. The men also carried paraffin which Shackleton writes was used to fuel an improvised oil-lamp. I wasn’t able to determine what ‘flamers’ and ‘blue-lights’ were though they could have been signal lights or flares, so perhaps they also burned petroleum.

The small Primus stove was used to heat up food and melt ice for water. On the rolling seas encountered on their trip, the men had quite a time trying to cook while holding the pot so it wouldnt spill. When the boat was encased in ice and in danger of sinking, the stove was even used to melt ice so that the water could be bailed out. ‘Prickers’ refers to the tiny tools used to clean the stove and keep it functioning. After a particularly close-call with a giant wave, Crean needed to clean the stove of clogs and get it working again. Without hot milk, food and water, the men would likely not have survived. Two stoves were taken with one as a spare.

The Nansen cooker was a collection of pots, pans and mugs used to cook food and heat drinks. The 2-gallon pot which they made ‘hoosh’ with - a sort of stew of pemmican, biscuits, and ice or water - was also used to bail water out of the boat on occasion.

Sleeping bags stuffed with reindeer hair were brought along to keep the men warm, but these were nearly always wet. The reindeer hair became a problem, too, and it smelled terrible and got everywhere including their food and nearly choked the men when they tried to sleep. Six bags were brought along so that each man could have his own but later Shackleton suggested using three as mattresses. The only area to sleep was below the canvas decking on top of a pile of rocks used as ballast. Eventually a few bags were tossed overboard to lighten their load.

The men took whatever spare clothing they could find including socks and some gloves. Unfortunately their warm weather Artic gear wasn’t made for the sea and only trapped the moisture, keeping the men continually soaked and cold.

Shackleton wrote that they took blubber-oil aboard. Lansing describes how Green and Orde-Lees rendered “some blubber into oil to be poured on the sea in the event that they had to heave to because of extremely bad weather.” I’m not entirely sure how this works but apparently pouring oil on rough seas can make sailing easier.

Food.

“It was much easier to face danger on a reasonably full stomach”, Lansing writes. As long as the men had something to eat they could face almost anything nature threw their way.

Provisions aboard the James Caird were simple. The men ate sledging rations made of dried beef and fat originally intended for the expedition’s dogs, prepared either hot or cold; nut food, a mixture of dried nuts and maybe fruit and other ingredients; biscuits, sugar, milk, and salt. Food gave them the nutrients they needed to survive but also kept them warm. On extremely cold days the men were allowed extra sugar and hot milk.

Shackleton said “our meals were regular in spite of the gales” since they needed food to maintain their well-being during the extreme conditions. Shackleton writes:

“Breakfast, at 8 a.m., consisted of a pannikin of hot hoosh made from Bovril sledging ration, two biscuits, and some lumps of sugar. Lunch came at 1 p.m., and comprised Bovril sledging ration, eaten raw, and a pannikin of hot milk for each man. Tea, at 5 p.m., had the same menu. Then during the night we had a hot drink, generally of milk. The meals were the bright beacons in those cold and stormy days. The glow of warmth and comfort produced by the food and drink made optimists of us all.”

While on Elephant Island the crew melted ice for water to be brought along in two casks. Ice was brought to supplement the water. When the Caird set off from Elephant Island, one of the casks went overboard and was partially damaged. Later they discovered that the damaged cask contained sea-water. When they were nearly out of water they drank the brackish water which did nothing to quench their thirst. Shackleton decided they had to land soon or risk dehydration.

Recipe: How to make “Hoosh”.

Navigation.

With the necessary food and equipment accounted for the remaining gear was allocated to the all-important task of navigating to South Georgia Island. Binoculars, Worsley’s sextant and another from Hudson, at least two compasses, and charts including a blueprint map of South Georgia, Worsley’s navigation books, and an almanac. Worsley also carried a chronometer around his neck, the last of 24 aboard the Endurance.

A sea-anchor helped the crew navigate the rough seas and later to keep to the shore of South Georgia when wind threatened to blow them off course. The anchor was eventually lost.

Shackleton writes that they brought with them an aneroid, or barometer, but I found no mention of it anywhere.

A note on Worsley’s navigation:

Worsley had the difficult task of making sure they were on course for South Georgia. Worsley had already successfully navigated them from the ice to Elephant Island. Worsley wrote:

“To tell the truth there had been a large element of luck in making this landfall. I had been very anxious, for our lives depended on reaching land speedily.”

For the trip to South Georgia, Worsley used a combination of dead reckoning and sextant navigation. Dead reckoning involves estimating one’s location based on speed, time and direction, providing your previous location was correct. Sextant navigation involves finding one’s latitude and longitude by measuring the sun and horizon. Due to poor visibility Worsley couldn’t see the sun and because the boat was “jumping like a flea” he couldn’t find the horizon either. Worsley did the best he could, the men steadying him while he took his sightings and made his estimations. Since he wasn’t confident in his measurements, Shackleton decided to aim for the western side of the island in case they sailed too far past the east side’s whaling station. Worsley got them to within 16 miles of the western tip of the island; a bulls-eye.

During the expeditions to locate the Endurance shipwreck Mensun Bound based their search grid off Worsley’s coordinates of where the ship sank. Bound spent considerable time studying Worsley’s navigational skills and diaries. In The Ship Beneath the Ice, Bound writes that once the men left the ice, they were in Worsley hands since Shackleton wasn’t nearly as gifted a navigator as Worsley and the “lions share of the credit for their survival really belongs to him.”

Notable items not included.

Not included in the list but perhaps the most important - the James Caird itself. The 22.5-foot long boat began life as a whaling ship brought along on the. When the crew abandoned the ship, they took it’s three boats with them. Carpenter Vincent McNeish modified the boat for open-ocean sailing, including raising it’s sides, reinforcing the hull, adding a mast and sails, and a makeshift decking so the men would have somewhere to sleep. Shackleton christened the boat after the Scottish manufacturer who contributed funds to the expedition. The James Caird now rests at Dulwich College.

Crucial to their voyage was ballast to make the Caird less-likely to overturn in rough seas. 2000 pounds was added which included bags of sand, blankets, and rocks.

A water pumper was brought to prevent the boat from sinking. Pumping water was a difficult affair which left the men’s hands cold and frostbitten.

An axe was used for breaking ice off the boat and later was used by Shackleton and two of the crew on their mountain crossings of South Georgia.

Shackleton brought a long a double-barreled shotgun and shells for hunting.

A medicine chest with gauze, cream, tape and other items.

Lastly, their diaries and notes without which we would not have as many details about this part of their trip.

In 2013, explorer Tim Jarvis recreated the epic voyage from Elephant Island to South Georgia with a recreation James Caird and period equipment.

Once the men left the ice their fates were tied to the sea. They could only take what they could fit in the boats. They were one step closer to finally being rescued once landing on Elephant Island. Shackleton then made the impossible decision to risk everything in an open-ocean crossing in a modified whaling ship, to sail 850 miles through some of the toughest seas anywhere in the world. And they made it. When Shackleton, Worsley and Crean finally reached the whaling outpost, men who sailed the Antarctic seas all their lives lined up “to shake the hands of the men who could bring an open 22.5-foot boat from Elephant Island through the Drake Passage to South Georgia.”

When I read Shackleton’s list and started thinking about how each item played a crucial role in their voyage, I realized that it told a story of what the men expected to encounter and how they hoped the trip would turn out. They made their preparations, they gathered their equipment, they no doubt steeled themselves for what they knew they would encounter. They also had to be prepared for both sea and land. Of course, these items mean nothing without the six men who gave it their all so that they could rescue their companions still stuck on Elephant Island. They made it to South Georgia because they had to. Shackleton’s list demonstrates what can be done with determination, preparation, and sheer willpower.

Until next time,

Keith.

Sources:

Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Journey, Alfred Lansing.

The Ship Beneath the Ice, Mensun Bound.

South!, Ernest Shackleton.