Tchad Blake's Lessons on Creativity

The recording & mix engineer’s creative use of ambient sounds and unconventional recording methods can be applied across artistic mediums.

Having been involved with music one way or another for the last 30 years, I’ve drawn an endless amount of inspiration and creativity from writing, performing, and recording music. I’ve always been interested in the art of recording a band and the record mixing process. How this usually goes is: I get hooked on a song or band, I research how they recorded something, mics used, instruments, etc. I go down the rabbit hole. I suppose that’s how I first learned about Tchad Blake, who mixed some of my favorite records. Recently I watched an interview with Blake where he drops some creative wisdom useful for any medium from music to writing.

But first, check out some of his stuff:

Tchad Blake has mixed countless records across a wide spectrum of genres, from rock, pop, jazz world music and more. His work features a gritty realness produced from creative recording and mixing techniques. Blake pioneered the use of binaural recording and his inventive use of distortion on nearly every element of a song created a new sound.

Before we move on, let’s stop for a moment and define mixing.

After a band or musician writes and records a song or album, the artist or producer might hire someone who wasn’t involved in the recording process to mix the song. With fresh ears from not having worked on the project previously, the mix engineer, or mixer, sits down at a large mixing console (or a computer), and balances all the ingredients of a song, literally ‘playing’ the instruments and vocals like an orchestra. More vocal here, less drums there, a bit more clarity on the guitar, less rumbly bass, and so on.

Believe it or not, mixing is the part of the recording process which can really make the song shine; in fact, a song usually doesn’t even sound like a ‘song’ until it’s mixed (mastering, another type of ‘mixing’ which also adds to the sound, is the final step before distribution). A mix engineer takes a static recording and gives it life. To clarify: a great mix will do nothing for a bad song; the musical performances by the band and the song itself have to shine before a mix can do anything for it.

Some mixers are incredibly transparent and you might not even notice they worked on the track, while others have a ‘sound’ that gets stamped onto the song. Tchad Blake falls into the latter group. I can usually hear right away if Blake worked on a song.

Looking back on his career in an interview with Audiopunks, Blake discusses his creative approach to mixing and recording music. In an area of the music industry often dominated by technical jargon focusing on gear instead of art, Blake talks about mixing like a musician rather than an ‘engineer’. He describes how he wrings all the emotion out of a song so it can reach people across the world. Upon beginning a new project, Blake starts ‘riffing’, just throwing up the faders, trying things out, and making mistakes until he discovers something that sounds and feels right to him. Not thinking so much as feeling.

The part of the interview which compelled me to write this blog comes at around the ten-minute mark:

“I got started in audio by going just taking a mono cassette tape recorder and a microphone and waking up… I'd be going to school and I'd wake up in the morning and put a 90 minute cassette in and I'd have a pack of 90 minute cassettes i'd put that in, hit record, I'd get out of bed go take a shower, go downstair,s I get in the car, you you'd hear all the doors open and closed, and the car, I drive to school… 45 minutes later…turn over the tape and then after that I put in a new tape and by the end of the day, I had so many hours of recording, and…sad but true, I'd sit there and listen to it late at night and I found that really - it’s a contrast - I’m hearing outdoor sounds indoors in my room sitting on my bed at night and that to me is surreal.”

Hearing Blake describe how he used to record everything during his daily life, is fascinating to me, and sheds light on his approach to mixing. He says that he’s drawn to music which incorporates ambient or nature sounds, like Pink Floyd who used various field recordings on their albums. Blake explains that hearing ambient noises attracts his brain, like a hunter keenly aware of any movement. He also uses distortion and ambient noises to ‘mess things up’, to make them less sterile sounding, as a studio recording can often sound, and inject some life back into the recording.

Blake exploits the brain’s hardwiring while crafting a mix, using the chemical responses of fight or flight to keep our ears and brains active and engaged, like a hunter searching for movement or a photographer focusing on light and shadow. He doesn’t just want to make a song sound nice and pretty. He wants it to grab you, shake you, throw you in the dirt and pick you back up again. He understands dynamics and contrast, balancing light and dark, distorted and clean. Blake’s mixes sound surreal, like a dream, larger than life. The song sounds ‘real’, so it feels real. It’s interesting to note that Blake keeps coming back to analogies which describe how the eye works while talking about audio, as if our ears are ‘eyes’ for sound.

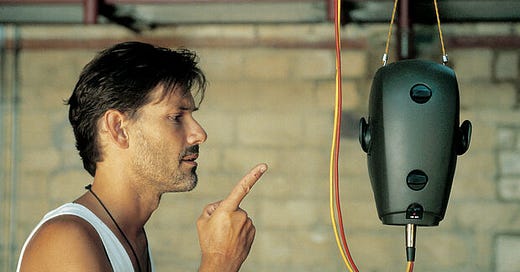

Blake’s wizardry in the studio is discussed on recording forums like the stuff of legend: using a dummy head with binaural mics inside to mimic human hearing; recording a bass drum through a series of pipes and hoses to create a weird ambience; running instruments and vocals through guitar pedals for distortion; walking around caves and recording the resonance. All of these tricks serve to add a life-like quality to the recordings. For Blake, all those years of recording the sounds of daily life and then listening back to them must have trained his ear to become attuned to certain frequencies and resonances, as well as the odd ‘errors’ inherent in such a recording; recording a loud car or door slamming on a cassette tape might have caused the tape to distort due to the excess in volume. To Blake, this means the recording was ‘real’, not perfectly captured in the pristine laboratory-like environment of the recording studio, but rather just the natural way our ears and brains hear sounds. Blake looks at mixing as a creative tool, shaping and sculpting sounds with experimentation until he reaches something which excites his brain’s sonic responses.

Blake offers the following lessons creativity:

Experiment. Don’t be afraid to try new things, to mess stuff up.

Go with your gut. Don’t think, feel. We’re going for emotion here not what looks or sounds right, but rather what feels right.

Play on our brain’s natural responses to input from our five senses. Go for a visceral response to the music, art, movie, or story. (I think of how Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is just overall unsettling but you can’t quite put your finger on why.)

Add ‘realness’ to your work with contrast, mistakes, or ‘happy accidents’.

Emotion is the ultimate goal.

It’s easy to see how the above can be used in a musical context or even a movie. But how might we apply Blake’s methods to writing? How can our writing invoke a visceral response?

A few examples come to mind:

Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House is downright creepy; the language, the pace, the descriptions of the house. It’s like her words are haunted.

Thrillers often employ the use of a ‘ticking clock’ scenario - the protagonist only has eight hours to save the day. This can create a rushed or anxious feeling while reading.

J.G. Ballard was heavily influenced by surrealist painters and called himself a ‘surrealist writer’. His writing captures an odd dreamlike, or hyper-realistic state.

I’ve also read about how some writers will listen to the same song on endless repeat while working on a particular scene or novel. I wonder how this influences one’s writing. Does it help them capture a certain feeling or state of mind which they can use to transport themselves into the world they’re crafting on the page? This seems similar to Tchad Blake’s use of natural ambience and distortion to create a certain mood or visceral response in his music.

For me the studio is a fantasy world, a place to make things happen that couldn't possibly happen in real life.1

Wow super interesting stuff. And I will keep an ear out for some of his unique methods next time I’m listening to any of the tracks he has mixed. Thanks Keith